igital download, 2025, available from New Focus Recordings, www.newfocusrecordings.com, or from Bandcamp, www.newfocusrecordings.bandcamp.com

Reviewed by Ross Feller

Gambier, Ohio, USA

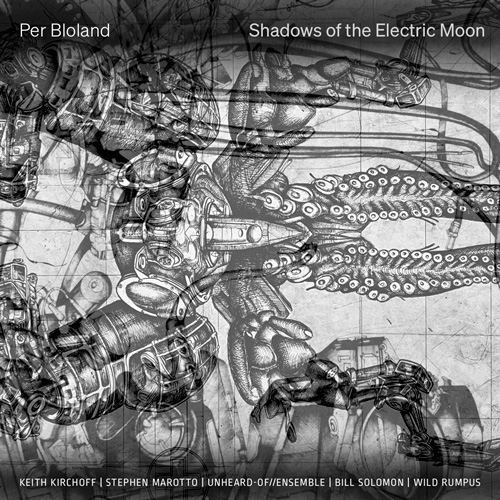

Per Bloland’s latest album Shadows of the Electric Moon, on New Focus Recordings, contains five instrumental and electroacoustic works. Composed between 2013 and 2021, the music on this album is based upon two through lines: fictional narratives and the composer’s software programming, used to process sound and integrate the electronics parts into the overall work. According to the liner notes, the interaction between these two through lines “is highly inventive in its subtle modulation of both instrumental and electronic textures, while unfolding within narrative, dramatic structures.” The composer’s custom made processing software largely serves to foreground subtle or idiosyncratic instrumental timbres, which he does a fine job developing.

Per Bloland’s latest album Shadows of the Electric Moon, on New Focus Recordings, contains five instrumental and electroacoustic works. Composed between 2013 and 2021, the music on this album is based upon two through lines: fictional narratives and the composer’s software programming, used to process sound and integrate the electronics parts into the overall work. According to the liner notes, the interaction between these two through lines “is highly inventive in its subtle modulation of both instrumental and electronic textures, while unfolding within narrative, dramatic structures.” The composer’s custom made processing software largely serves to foreground subtle or idiosyncratic instrumental timbres, which he does a fine job developing.

The composer has written that he is drawn to “the idea of diving into a piece of literature and extracting specific qualities, concepts, or structures to use as musical guides.” He ties this idea into what scholar Siglind Bruhn has called “musical ekphrasis,” a method of translation from a non-musical medium into music. Much of Bloland’s recent work is inspired by, or based upon, the writings or life of Norwegian author Pedr Solis.

The first piece on this album, “Los murmullos” for piano and electronics, is based upon a dystopian novel written by Juan Rulfo between 1953 and 1954. The electronics part was produced “using a physical model of the Electro-Magnetically Prepared Piano - a device Bloland designed where a computer sends signals to electro-magnets that vibrate the strings of the keyboard.” Partly, his intent is to create a device that is able to transform the acoustic piano into a synthesizer. Bloland calls his physical modeling device the Induction Connection, which is now widely available in IRCAM’s Modalys software.

“Los murmullos” opens with the sounding out of powerful and resonant low octave piano tremolos or pulsations. Different overtones pop out, depending on the type of attack or dynamic. We hear a repetitive right hand part against the previously introduced, low octave material. From the beginning it seems clear that the composer is going to explore the friction between highly repetitive and dissonant materials.

The use of electronic processing is, at first, subtle and mostly impacts our hearing of resonance. This is described in the liner notes as “a halo of sound.” The piano part oscillates back and forth between abrupt spasms of repetition and virtuosic, atonal, linear, almost free jazz elements that in combination make for some edgy listening. Some reference points include piano works such as “Lemma-Icon-Epigram” by Brian Ferneyhough, and others by Karlheinz Stockhausen, Pierre Boulez, and Cecil Taylor.

In this piece, the listener encounters a wide variety of sounds including:

split and detuned electronic sounds, scream-like vocal sounds, and noise elements that, at times, threaten to mask everything else. At times Bloland’s processing techniques make the piano resemble a distorted guitar. The cumulative distortion is periodically cut off, leaving silence or reverb trails in its wake.

The tight coordination between the piano part and electronics reminds me of the “Synchronisms” series for instruments and tape by Mario Davidovsky. A significant distinction between the two is that Davidovsky employs his electronic parts to fortify his pitch-centric material, whereas Bloland’s approach is focused much more on texture, and occasionally refers to industrial noise music and current video game sounds.

I would also argue that Bloland’s use of electronics is better integrated into the composition as a whole. For example, it doesn’t dominate the acoustic, instrumental parts, but neither is it innocuous. This all adds up to an unstable sonification of dystopian elements. This composition’s successful integration of sound, processing, and raw energy makes it one of the best works on the album, but it is not for the faint of heart.

“Points of Light in Shadow,” the title of the second piece, is taken from a novel by Pedr Solis. This piece uses two sound exciters strapped to a cello, which are fed sounds from Bloland’s program called MaxOrch. This program utilizes samples to emulate sounds, instruments, or specific instrumental techniques. In the case of “Points of Light in Shadow,” the composer’s source material for the electronics consisted of recordings of bass clarinet and bassoon multiphonics. This material adds “an element of breath to the cello, as if it is an augmented bowed-wind instrument.” Different from the first piece, these small devices cause the body of the cello to vibrate, as opposed to the strings of a piano. The cello part focuses on delicate sounds and techniques such as harmonics, trills, and tremolos.

The third work, “Displacement Pressure,” for clarinet, violin, violoncello, piano, and electronics was written as a reflection on the issue of the lack of affordable housing. The title refers to the ‘pressure’ to gentrify an area of a city, etc. This inevitably causes parts of the population to be displaced. The sounds used in this piece were extracted from construction site recordings from Cincinnati, and are, at times, sonically imitated by the quartet. About this piece, Jon Sobel writes in the liner notes that Bloland “threads together nine minutes of eccentricity that feel as if they carry an obscure internal logic.” To the extent that Bloland’s program notes point to a common problem in city planning, perhaps listeners will contemplate worthy solutions to the unintended consequences of ‘revitalization’ efforts. But, otherwise, it is difficult to imagine that the act of listening to this piece will spur someone on to fight the power. Interestingly, this piece contains more musically conventional trappings than some of the other works from this collection.

Based on a novel by Bloland’s favorite Norwegian writer, Pedr Solis, “Shadows of the Electric Moon” for snare drum and sound exciter “explores various ways of altering its otherwise limited timbral palette.” The snare drum itself is played in an unconventional manner, upside down with the snares exposed, and ‘prepared’ with a crotale and cymbal. The sound exciter is connected to the drum and receives frequencies from a computer. This process produces a variety of sounds and suggested spaces. Some are humorous. Others remind one of mechanical, construction noises such as sawing, hammering, or drilling. Overall, we encounter a fast shifting kaleidoscope of sonic fragments and gestures. About half way through the piece we hear vocal timbres, amplified via the drum membrane, which turns out too be an effective timbral modification technique. One might imagine choreographed movements to accompany these sounds, in the manner of Mark Applebaum’s fixed media piece “Aphasia.” Whatever the case, the Futurists would have greatly appreciated Bloland’s efforts in this piece.

In the program notes, Sobel states “the sounds feel mechanical, the music seemingly random.” This is generally true if we take any given slice of the piece and examine it. But as a whole, the linear formal structure, especially in a 13-minute work, becomes more and more predictable as the composition moves forward in time. All the interesting timbres may have been generated from contemplation of Solis’s novel, which takes place in a barren county in the far north of Norway.

I would have wished that Bloland had spent a little more time developing his interesting timbres. I haven’t read the novel but it seems fair to assume that someone stuck in this kind of barren landscape would have plenty of time to develop things. The Canadian pianist Glenn Gould once composed a radio documentary entitled The Idea of North, where he developed an experimental technique he called “contrapuntal radio.” This technique employed polyphonically layered voices on top of each other. Perhaps Bloland could have created something similar had he used multiple snare drums, or had he used extreme contrasts to produce a sense of virtual polyphony.

“Solis Overture,” the last work, functions as a kind of sketchpad overture for the composer’s opera Pedr Solis, which chronicles his life. It is scored for percussion, piano, electric guitar, violin, violoncello, and electronics. All of the instruments are amplified in a live performance but receive no additional processing. The electronic sounds are pre-recorded and played back by a laptop. The sounds suggest deep bass growling or whale song, multiphonics, and a feedback solo by Jimi Hendrix. We hear these sounds within a segmented formal structure, which is effective here due to the high degree of contrast between each section.

Sobel writes: “Solis Overture” returns to the industrial vocabulary of “Los Murmuloos,” this time derived from the instrument most associated with that genre, the electric guitar.” This final piece is closer to the industrial noise genre, without succumbing to that genre’s standard performance practices, such as the overuse of improvised, through-composed forms. “Solis Overture” is one of the most effective works on this album. The listener is kept guessing as to what will happen next. And the rapid pacing of events makes this element all the more poignant.

Bloland’s compositional practice on this album, including the incorporation of electronics, and the addressing of social and political issues in his work echoes aesthetic values from a younger generation of composers that don’t view atonality as a creed or imperative, but rather as a tool to achieve specific purposes, perhaps in combination with electronic processing.

Most of the pieces on this album use pauses as structural or formal markers. At times these breaks are needed to temporarily recover from an information rich texture. But their employment becomes predictable and thus, halts any kind of continuous development. Several of the endings seem to simply stop, without any sense of dissipation. The exception to this is “Shadows of the Electric Moon.” All in all, the minor weaknesses I cited do little to disturb the impression that this album is a significant contribution to current work being done with instruments and live electronics.