Cuneiform Records: 2 compact discs, streaming, and digital download, 2024. Available from www.cuneiformrecords.com and www. cuneiformrecords.bandcamp.com.

Reviewed by Ross Feller

Gambier, Ohio, USA

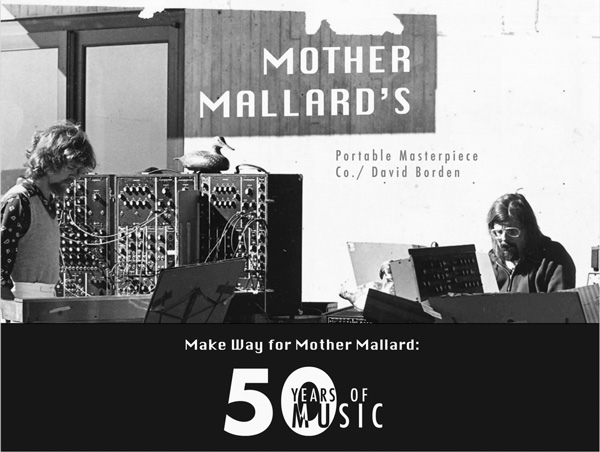

In the spring of 1969 composer-pianist David Borden founded one of the first synthesizer ensembles. Mother Mallard’s Portable Masterpiece Company was conceived in Robert Moog’s studio in Trumansburg, New York. The group began working with Moog’s analog synthesizer prototypes, learning to control their modular circuitry, and eventually creating a tightly structured approach to original, live music that was largely achieved using Moog’s Model A Minis.

In the spring of 1969 composer-pianist David Borden founded one of the first synthesizer ensembles. Mother Mallard’s Portable Masterpiece Company was conceived in Robert Moog’s studio in Trumansburg, New York. The group began working with Moog’s analog synthesizer prototypes, learning to control their modular circuitry, and eventually creating a tightly structured approach to original, live music that was largely achieved using Moog’s Model A Minis.

Make Way for Mother Mallard: 50 Years of Music is a two-disc cd set, released by Cuneiform Records, featuring Mother Mallard works from the 1970s through 1987. David Borden’s relationship with Steve Feigenbaum, Cuneiform Records’ founder, goes back decades when one of Feigenbaum’s previous labels sought to release an album of Borden’s work.

This two-disc set represents different recording eras and technologies. The first was recorded sometime in the late 1970s, when much of the music was newly composed. The second disc was recorded in 2019 and includes work from the middle 1970s through the middle 1980s. In addition to synthesizers, the first disc features the trumpet and the RMI (Rocky Mount Instruments) piano, while the second disc contains the Juno 60 and 106, Moog Voyager and Minimoog D, Fender Rhodes piano, acoustic piano, voice, and drums. It is fascinating to hear the changes in sound, conception, and instrumentation from the halcyon days of the early 1970s through the early days of consumer digital audio and MIDI.

Make Way for Mother Mallard begins with a convincing, timbrally-sculpted work entitled “Endocrine Dot Patterns,” which was composed in 1970. The endocrine system produces hormones that impact the growth and reproduction of various bodily functions. This concept appropriately serves as an overarching characteristic of not only this composition, but many of the other works from this collection. “Endocrine Dot Patterns” presents three Moog synthesizer parts and overdubbed trumpet tracks. The subtle changes of timbre and filtering, and plaintive trumpet sustains create a unique blend that is not repeated elsewhere in this collection. There is a palpable sense of experimentation and sonic exploration, which makes this track stand out. I hear the individual parts creating a diverse texture, rather than being tied to minimalist arpeggio patterns that are commonly found in many of the subsequent works. As the earliest work represented here, “Endocrine Dot Patterns” also provides a context from which to hear the subsequent works. This is a fine piece to open the listener’s ears to some of the subtleties of the succeeding pieces.

The next piece, “C-A-G-E I,” clocking in at 32:11 is the longest piece on this collection. It is also one of the most consistent. On the surface it comes across as a cross between Steve Reich’s and Philip Glass’s music. The intervals can be heard as derived from Reich, while the keyboard textures are from Glass. The repeated, additive patterns and canonic procedures are derived from both composers. By the time this piece was composed in 1973, Reich and Glass were well on their way to becoming household names. Glass had moved to New York City in 1967 and after hearing Reich’s “Piano Phase,” had already gravitated to a more rigorous, minimalist technique that began to yield works such as “Music in Contrary Motion” (1969), “Music in Fifths” (1969), “Music in Similar Motion” (1969), and “Music with Changing Parts” (1970). Reich, for his part, had already become engaged with phasing and simple audible processes in works such as “Come Out” (1966), “Piano Phase” (1967), “Pendulum Music” (1968), and “Four Organs” (1970).

But there is more to Borden’s work for Mother Mallard than a derivative of Reich or Glass. Glass’s early music was notoriously loud and virtuosic. The same can be said of Borden’s music for Mother Mallard, but with the caveat that it also contains a kind of raw, almost grungy, energy commonly found in rock music. This is one of the factors that make this music stand apart from its minimalist roots. A great example of this occurs in the bass lines found in Borden’s “Ceres Motion,” (from Mother Mallard’s Portable Masterpiece Co. 1970-1973) composed in the same year as “C-A-G-E I.” Invariably, my computer music students immediately recognize these lines and usually assume that the composition was created decades after its actual date of creation. In this respect, it is not insignificant that Borden refers to Mother Mallard as a band, not an ensemble.

“C-A-G-E I” was recorded at the band’s farmhouse studio in Enfield, New York. The music is as virtuosic as that of the aforementioned minimalist pioneers. Yet we hear a looser approach to group unity, without losing the transcendental effect of competently performed note streams. On rare occasion there sounds like an unintentional rhythmic or phrasing hiccup but they only serve to underscore the humanity heard on this recording. Interestingly, the early Mother Mallard band only consisted of three synthesizer players. Like other works from this period, the texture created in this piece sounds thicker than what might be expected from only three performers. This is a testament to the rich timbres they used and subtle approaches to oscillator tuning.

Shortly after the midway point, “C-A-G-E I” begins to pay homage to an additional minimalist music pioneer – Terry Riley, especially with respect to the canonic material, buzzing synthesizer sounds, and shifting timbres found in albums such as Rainbow in Curved Air.

By the end of “C-A-G-E I” certain pitches from the timbral maelstrom begin to pop out to the ear, much in the same way that occurs in Reich’s and Glass’s music – as byproducts of primary lines that come to the foreground because of dynamic and phrasing factors. The piece ends with a gradual fadeout wherein the music dissipates, yet doesn’t truly end in a traditional sense.

The bulk of Make Way for Mother Mallard is devoted to eight parts of a colossal 12-part work composed between 1976 and 1987, called The Continuing Story of Counterpoint, and released by Cuneiform Records on a three disc set at the end of the 1980s. This is a work that Feigenbaum calls “one of the most important documents” of American minimalism. Writer and radio host, John DiLiberto describes it as the “Goldberg Variations of minimalism.” Both sentiments adequately represent the grand gesture that resulted in The Continuing Story of Counterpoint.

Part 1 begins with a series of rapidly changing, pulsating and interlocking synthesizer patterns. These patterns sometimes traverse radical tonal shifts that are uncommon in straight-up minimalist music. Perhaps the use of the Juno and Moog keyboard synthesizers helped bring about these quick changes of tonality and texture.

Many of the interlocking patterns were rhythmically asymmetrical and would not be out of place in a progressive rock scenario. The patch timbres used were clearly based upon oscillators producing basic sine, sawtooth, pulse wave, etc. waveforms. The chordal changes impart a sense of active tonal movement. Against the pulsating surface patterns we also hear a series of sustained low register notes in augmentation that help supply an additional sense of counterpoint.

Part 3 sounds like it continues immediately from its predecessor, Part 2, but I can’t say for sure, since Part 2 is not included in this collection. Many of the same musical components from Part 1 are also included in Part 3, but in different registers, using different timbres. On occasion, the interlocking parts seem to be slightly out of sync for brief periods of time, similar to the kind of organic phasing that Reich uses in “Violin Phase” and “Piano Phase.”

Also, in Part 3 the voice is introduced, adding a significant aesthetic departure from the previous tracks. Meredith Monk’s work comes to mind, or parts of Glass’s Einstein on the Beach, however, here Borden has his singer intone the names of various well known contrapuntal composers including: Palestrina, Machaut, Dufay, Henry Purcell, Josquin des Prez, and Orlando di Lasso. The vocalist sings the names in an ironic, quasi-operatic style. I found this part to be oddly compelling.

“The Continuing Story of Counterpoint, part 5” uses a Fender Rhodes piano and electric guitar, in addition to the usual keyboard and synthesizer set-up found in the earlier parts. The keyboard parts are panned hard left and right, providing what might be described as a flange-chorus effect. The inclusion of the electric guitar, using soft distortion, places Part 5 within the progressive rock genre, and successfully so. This is no mere ersatz delivery of aesthetic goods. The fast tempo, in combination with quick arpeggios and interlocking patterns makes this part into a positively dizzying listening experience that concludes with a nice dose of guitar feedback.

“The Continuing Story of Counterpoint” Parts 7 and 8 don’t provide much that is substantially new. However, Part 8, recorded live at Cornell University’s Johnson Museum of Art, sounds like it uses an electric bass part, but the liner notes don’t mention this. It is possible that the bass part was played on the Minimoog D. If so, the performer successfully copied the transient and envelope properties of the electric bass to the synthesizer. Part 8 utilizes an array of two-note tremolos within a dense network of interlocking patterns not unlike the work of the French progressive rock band Art Zoyd (also available from Cuneiform Records). Part 8 is also the first work from this collection that was recorded recently in 2019. The engineering and post-production competence of the composer’s son Gabriel is in evidence in this track.

Composed in 1986, Part 11, for two pianos, provides a strong sense of change in light of the previous works on this collection. Since it doesn’t utilize electronics or computers I won’t say much about it. What I will point out is that the piano parts sound quite similar to the synthesizer patterns heard previously. The porting of these materials to acoustic instruments seems to diminish the uniqueness of the composer’s quirky praxis. In other words, the piano serves to ‘normalize’ the composer’s music. For some listeners, this will legitimize his work in their eyes/ears. For others, it will have precisely the opposite effect.

The last piece on this double-disc is part 12b of “The Continuing Story of Counterpoint,” composed in 1987 and recorded live in 2019 at Cornell. Besides the usual synthesizer setup the voice makes a reappearance and a drum set part is added to this mix. The keyboards play more dissonant intervals than found in the previous works. The tension added is palpable. The voice part is largely and sparsely used to provide an extra, sustained melodic line, using open syllables (la or ah). The vocalist (the same one as on the previous track) sounds strangely reminiscent of today’s AI voices, provided by some current software packages. The drum part provides a busy, ‘jazzy’ quality that was somewhat disappointing, at least to this listener. To alleviate my disappointment, I had to imagine what this part would sound like with a solidly, progressive rock drum part. In my mind, this would have connected the dots from the composer’s earlier work.

Make Way for Mother Mallard: 50 Years of Music represents an imperative that suggests that Borden’s music for Mother Mallard take its seat in the pantheon of minimalist icons. This music demonstrates that Borden led the way from a purist minimalism to one much more diverse, even including accouterments from the world of progressive rock. This two-disc set is, if nothing else, an important historical document that showcases a pioneer’s work that has not lost its relevance even decades later.