CD and Digital Download, 2023, available from Ravello Records and as a digital download from streaming services, RR8090, https://www.ravellorecords.com/catalog/rr8090/.

Reviewed by Ross Feller

Gambier, Ohio, USA

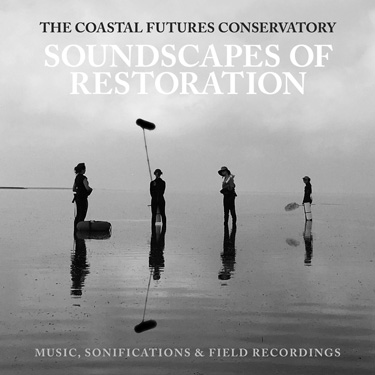

Spearheaded by Matthew Burtner, this recent Ravello release, Soundscapes of Restoration: Music, Sonifications & Field Recordings, contains 13 diverse works that conjure up images of habitats along the Atlantic coast. The Coastal Futures Conservatory, the initiative that inspired this project, resides at the University of Virginia, integrating the arts and humanities in an investigation of coastal change. The premise is stated in the liner notes to this collection: “The Coastal Conservatory urges us to consider our efforts of restoration and offers us an avenue for restoring coastal futures, a meditation on the music of the most integral barriers to the ever-pressing Atlantic. Soundscapes Of Restoration is both an exploration and a reflection, a listening experience that leaves one changed with the desire to make change further. It is a journey that cannot, and should not, be forgotten.”

Spearheaded by Matthew Burtner, this recent Ravello release, Soundscapes of Restoration: Music, Sonifications & Field Recordings, contains 13 diverse works that conjure up images of habitats along the Atlantic coast. The Coastal Futures Conservatory, the initiative that inspired this project, resides at the University of Virginia, integrating the arts and humanities in an investigation of coastal change. The premise is stated in the liner notes to this collection: “The Coastal Conservatory urges us to consider our efforts of restoration and offers us an avenue for restoring coastal futures, a meditation on the music of the most integral barriers to the ever-pressing Atlantic. Soundscapes Of Restoration is both an exploration and a reflection, a listening experience that leaves one changed with the desire to make change further. It is a journey that cannot, and should not, be forgotten.”

The title of the first work: “Virginia Barrier Island Soundscape: Listening to Climate Change and Resilience Part 1” spells out what is heard in Burtner’s field recording. Interestingly, and perhaps unexpectedly, there are many musical attributes that direct one’s listening. For example, the formal structure of the piece largely results from subtle editing of what sounds like different locations or times of the day in which the recordings were made. The water sounds themselves were much more varied than expected, closely resembling granular and physical modeling synthesis techniques. At times they sounded as if filters had been added or used to process the raw recordings. Presumably, this was not the case.

The next piece, “The Dreams of Seagrasses,” is uniquely composed for the EcoSono Ensemble and seagrass data sonification. The ensemble features an intriguing and wide variety of instruments including: pip, flute, trumpet, viola, and cello. In the program notes, Burtner explains: “This piece explores the photosynthesis and respiration of the seagrasses from two VCR datasets. It first sonifies data on seagrasses producing oxygen and consuming carbon dioxide, which cycles across the day as a result of daylight and other environmental factors. The metabolism was measured every hour for a period of two months; consequently, we hear the cycles of day and night across 24-hour periods and grouped into weekly harmonic cycles. The piece overlays that sonification with another sound created from data on the chemical makeup of the seagrasses themselves. The chemical data was collected across a period of seven years. The two datasets together offer an impression of the changes in the seagrasses across varying scales of time. The sonification allows a listener to gain a sense of the complexity of the system across years, months, days, hours, and seconds.”

The listener might have questions about how the composer utilizes this kind of data sonification. For example, how does the composer represent datasets from one time scale into a much smaller timeframe, such as the six-minute duration used in this piece? And how might data sonification make convincing music? The liner notes state: “Burtner’s melodic overlay of the more chaotic swirl of sonified data permits the listener to imagine the grasses improvising a songline into their version of a coastal future. Each note of that songline is dependent on temperatures staying within a certain range — 28C water temperature seems to be a key threshold — and the barrier island marsh deposition keeping pace with the overwash of the next big storm.” Musically speaking what is heard is textural stasis, achieved through the use of a drone and pitch matching between the ensemble and the recorded track. Some of the ensembles punctuated gestures are iconically related to the recorded track. We also hear a mournful melody superimposed over the drone that, perhaps, symbolically represents the drastic changes discussed in the liner notes, or the sense of habitat loss. This piece can aptly be described as programmatic, since without reading the composition or listening notes provided in the album’s materials, it seems unlikely that the listener will perceive what the composer discusses within the sound itself.

Composed by Chris Chafe, the next work, is the first of four compositions by Chafe, scattered throughout this collection, that employ ensemble and coastal data sonification from 100 years of tidal records from the southern end of San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge. It is a reworking of a previous piece that included a video part and the composer improvising on the Celleto along with the sonification audio. Each Coastal Conservatory variation, about three and a half minutes in length, is titled “The Metered Tide,” followed by a distinct refrain subtitle number. Members of the EcoSono Ensemble individually improvise with the recorded Celletto and sonification versions. The liner notes explain how this all works: “In post-production, Chafe’s software — through which the audio mix is generated automatically — follows the original tidal data. The sonification signal was thus the conductor and the mixer, with the human musicians responding to it and being layered by it. The output we hear on this version is a mixed compilation of the seven lines, in which the cuts are determined by the tidal data.”

This first part, titled “The Metered Tide: The Metered Tide,” features the EcoSono Ensemble performing on pipa, flute, soprano saxophone, trumpet, viola, cello, and piano. The composer builds textural stasis through drone materials, extended techniques, and timbral blending. Abrasive, percussive materials continually disrupt this sense of stasis, redirecting the listener from their comfortable perspective. Similarly, “rendering data into sound can restore attention. In an information economy organized for ocular reception, attending to a record of change aurally rather than visually can startle minds accustomed to graphs and charts. Sonifications can help us imagine relations or temporalities that are difficult to understand, or attend in a new way to rates of change so visually familiar that they are quickly dismissed.”

“The Metered Tide, Refrain 1” begins with freely improvised constellations of notes played on the inside of the piano and by the string instruments. The flute softly echoes this material in the background. After about 60 seconds this texture radically changes, bringing the flute into the foreground playing sustained pitches that subtly glissando up and down. The other instruments join it performing a wide variety of fragmented materials, repeating like broken cogs in a wheel.

“The Metered Tide, Refrain 2” begins with more flute sustains, but the way in which some of the notes abruptly cut-off or change their position in space imply that recording or processing techniques were used to achieve this effect. The liner notes help us to understand what might be going on: “In final production, the tidal record in turn plays the musicians. Software algorithmically reads the dataset to select which of the musicians’ improvisations are played when. As the data from a century of tides mixes human responses, The Metered Tide thus also exemplifies the possibility of responses to coastal change in a more-than-human assemblage of composers.”

“The Metered Tide, Refrain 3” begins much like Refrain 2 but with the cello taking the flute’s role. This is followed by ‘underwater’ sounds that sound as if they were processed via granular or comb filtering techniques. The combination of analog, acoustic sounds with electronic processing is exquisite, and serves to heighten attributes from both worlds. At times the overall, effect suggests vocalization through a conical bore, recorded close-up.

Composed by Eli Stine, “Where Water Meets Memory (Coastal Mix)” is an electronic, ambisonic, environmental and instrumental composition that contains recordings of a soprano voice, violin, and cello. According to the composer: “The first recording you hear is of natural and restored oyster reefs, made using hydrophones off the coast of the seaside town of Oyster VA. These sounds are now known to help orient young, swimming oysters and other organisms in their search through murky waters for a vibrant oyster reef. You will then hear electronic music transformations of those recordings, in which computer technology processes the rhythms and pitches of the original reef recordings into completely new timbres, melodies, and harmonies.” The pristine recordings, subtle attention to spatialization, and the use of rich, subwoofer frequencies make this piece standout. Compositionally, the meticulous integration of this work’s component parts is highly effective.

“The Noise Parade/Die Lärmparade” is a piece by Francisca Rocha Goncalves that features field recordings and electronics. It was originally created for the Your Ocean Sounds Hackathon, sponsored by the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin. The composer used “recordings of underwater pile driving sounds, explosions, boats, and some biological sounds from whales and fish.” The introduction sounds ominous because of a mixture of subwoofer tones (perhaps whalesong), dripping water sounds, and periodic thumping (the pile driver?). We also hear mysterious scratching tones, rapid woodpecker-like tapping, and several explosions. The explosions disturb the underlying idyllic atmosphere. The composer connects this to noise pollution. “This piece approaches the concept of masking, one of the main issues regarding underwater noise. Its core message is awareness of noise pollution. While biologic or geologic sounds are part of the natural elements of an aquatic environment, and all marine life is well adapted to them, anthropogenic noise and human interference have started to affect some aspects of animal communication. Because they essentially interfere with the frequency ranges of communication in many marine species, these newly introduced anthropogenic sounds disrupt the underwater environment.”

Matthew Burtner’s piece, “Crab Flutes” features the flute and crab field ecoacoustic recordings. The premise for this piece is intriguing with respect to its concept and realization. Along the banks of Virginia’s Eastern Shore, fiddler crabs burrow in the mud to create their homes. “Each burrow is different, dependent on the body size and digging techniques of the crab as well as the conditions of the mud. These small habitats are called “flutes;” and like the musical instrument, they resonate at a specific frequency when air is blown across the opening. By placing a tiny microphone inside these crab flutes, we can listen to the sounds of the world (mostly the wind and sea) resonating inside the little cavern… This music features a field recording made inside one of the crab flutes playing throughout, and the harmony, melody, and rhythm of the composed music were derived from the crab’s habitat.” The result includes flute melodies that apparently, naturally, fall into two minor keys. So, we hear notes from these keys slowly moving through the texture, beneath percussive scratching sounds, which are recordings of the crabs moving about in their homes.

In “Piano Etude No. 2: Tidal Flow” by Chris Luna-Mega, a MIDI piano is used to sonify data derived from the Long Term Ecological Research project in Oyster, Virginia. Tidal measurements were mapped onto the piano, at a rate of one pitch per day for each hand, from an eight-year period. “The poetic intention is for a pianist to embody the tides.” The sonic result is quite active, split between a field recording of the ocean and the piano part. The latter is mostly continuous, within a narrow octave range, at a tempo that would be impossible for a human pianist to perform. Hence, the result resembles the player piano work of Conlon Nancarrow, but with, arguably, less aesthetic interest due to the lack of timbral or structural variation.

Burtner’s “Oyster Communion” offers the listener a variety of timbres and novel combinations, using a sung voice, the EcoSono Ensemble, and close-up recordings of oyster shells, which the composer meticulously records and moves around in a virtual space. The liner notes explain: “The complex range of crackles and pitches of oyster reefs on the Virginia Shores offers clues to the health of these ecosystems. Snapping shrimp make high, crackling sounds, while fish make lower sounds. The oysters themselves emit low crackling sounds as they open and close to filter food particles out of the water. The lowest sounds, made by waves and currents moving over the reef, tell us about its structure. On the oyster reef, we hear all this activity combined together into one bustling soundscape. The field recording was made using a stereo hydrophone technique, creating a highly spatialized and dimensional impression of this unique underwater environment. The field recording is set with an ensemble of dead oyster shells played by the ensemble as percussion instruments. The shells are struck and rubbed together to articulate their resonance. Performed in counterpoint with the field recording, we hear across generations of oysters, the living animals, and the shells left by the deceased.” Add a vocal part in which the singer sings a song about oysters, and the overall sonic result is as intriguing as Burtner’s conceptual and compositional processes.

“Fluido Therapy #1”by Francisca Rocha Goncalves incorporates field recordings and electronics. Like her other piece on this collection, this work is also ‘about’ noise pollution in aquatic environments. But unlike “The Noise Parade” this composition is understated and more ominous. This piece “proposes an investigation of different tones resembling anthropogenic activities that often overlap and mask important biological cues for bioacoustics.” We hear subtle recordings of various types of noise pollution that effectively mask the sounds of communication between aquatic species. The notion of therapy, here, takes on at least two meanings: what the listener hears and what the listener might conceive of as a remedy to this type of noise pollution.

The last piece, “Virginia Ghost Forest Soundscape: Listening to Climate Change and Resilience Part 2” bookends this collection with another field recording by Burtner. In this work, the sound of water or wind plays a much smaller role than in the first piece. Instead, we hear the lively presence of a forest, full of birds and insects, some of which sound as if they came very close to the microphone.

This album attempts to raise consciousness of concepts such as ecological restoration through audio that captures habitat resilience, while employing data set sonification and field recordings to offer listeners audio maps of what is at stake if these settings were to vanish. The concept of restoration is a significant part of this process. “Each piece offers a form of cognitive restoration. The tracks restore the mind’s attention to world-making practices of non-human organisms, beings, and forces.” And, as such, they remind us that “paying attention can and should be the basis for crafting better possibilities for shared life.” Whether this attention will do anything to change the course of events, remains to be seen, and heard. This is, of course, true for much politically-inclined music or what Paul Hindemith called Gebrauchsmusik. In the meantime, this album contains well-crafted and intriguing recordings and music by which we might contemplate the beauty of the natural, but also, virtual worlds.