On the evening of April 24th, 2021, a concert celebrating the music and career of John Bischoff was held in Oakland, California at Mills College’s Jeannik Méquet Littlefield Concert Hall.

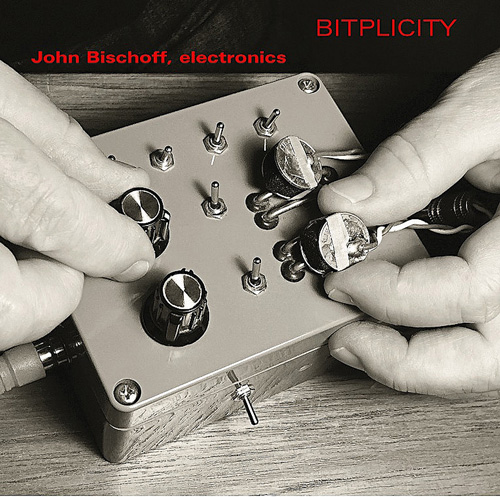

Bitplicity: a compact disc and digital download, 2021, available from Artifact Recordings, San Francisco, California: www.artifact-ubu.org, and from Bandcamp: www.bandcamp.com/.

Reviewed by Ralph Lewis

Urbana, Illinois

On the evening of April 24th, 2021, a concert celebrating the music and career of John Bischoff was held in Oakland, California at Mills College’s Jeannik Méquet Littlefield Concert Hall. Streamed online and presented to a limited in-person audience, it showcased examples of his decades-long experimental practice with live electronics and network music found in his solo compositions and as a member of the League of Automatic Music Composers (1978-1983) and the Hub.

On the evening of April 24th, 2021, a concert celebrating the music and career of John Bischoff was held in Oakland, California at Mills College’s Jeannik Méquet Littlefield Concert Hall. Streamed online and presented to a limited in-person audience, it showcased examples of his decades-long experimental practice with live electronics and network music found in his solo compositions and as a member of the League of Automatic Music Composers (1978-1983) and the Hub.

The first half of the concert featured Bischoff performing his solo compositions Bitplicity (2020) and Visibility Study (2015). Although these are recent works, they reflect aspects that are audible throughout Bischoff’s catalog. Each has a soundworld that is simultaneously fastidious and unruly. Specifically, each one centers around a seemingly ungovernable, indeterminate sonic force that is redirected carefully and subtly, through Bischoff’s practiced performance. As he himself describes in the liner notes for his recently released album Bitplicity: “the starting point for the composition of these pieces begins with pulse-wave oscillators sounding in audio and sub-audio realms that are animated by performer actions–primarily the momentary shorting of conductive points in each circuit.”

In attending the concert virtually, the camera allowed for a more intimate, close-up experience of watching Bischoff interact with his table’s set-up, which included a laptop and some small homemade devices. The chirps and pops at the beginning of Bitplicitywere carefully disrupted and redirected throughout its duration. New densities and trajectories arose out of the patient handling he brings to his materials. This patience is a part of the strong influence David Tudor’s music has had on Bischoff and his longtime collaborator Tim Perkis. In reflecting on their time in the League of Automatic Music Composers, they have written about being inspired by Tudor’s “powerful notion…that the primary job of a musical composer/performer during performance was listening, rather than actually specifying and creating every sound that happens in the performance.” In this performance, Bitplicity’s successive periods of Bischoff’s listening were followed by engaging with the circuit. The outcomes of this included drawing out fuller versions of the basic material, unexpected drops and leaps in register, and the eventual flattened sustains at its end.

While keeping in the same spirit and general design of the first work, Visibility Study displayed an emphasis on the discontinuities Bischoff’s music seeks out. In lieu of Bitplicity’s fine adjustments, demonstrative knob turns making broad timbral sweeps through oscillator tones were part of its initial material. They were combined in layers with a more active use of live sampling creating recurring time-keeping gestures. Within this richer presentation, so much depended on the angularity of the gestures and how more or less disruptive or grainy various points within the sweeps were at any given moment in their small trajectories. Here and in Bitplicitybefore it, the live qualities and performance practices of Bischoff’s music make it a subtle, communicative affair even with the abstracted, unstable materials.

These exact performances from the first half of the concert appear as the first and last tracks on Bischoff’s album Bitplicity. Much like the program notes for the concert, the album emphasizes that these are live performances. The other works on the album are “Circuit Combine” (2013)and “Level Shift” (2017). “Circuit Combine” recalls Bischoff’s earlier“Audio Combine,” perhaps as a reconfiguration of the earlier work’s processes.“Level Shift” meanwhile is the calmest of the works, leaning into similar creative tactics using drones as their musical material.

The second half of the concert featured a performance of “League Trio”by Bischoff, Perkis, and current Mills Center for Contemporary Music director James Fei. As the title suggests, it is inspired by the live, networked microcomputer works and improvisatory practices of The League of Automatic Music Composers (whose members included Bischoff and Perkis as well as Rich Gold, James Horton, and David Behrman).

The sonic terrain of “League Trio” was different from Bischoff’s earlier set, even after acknowledging the new personnel and equipment on stage. Interlinked through audio pathways and sharing data via OSC, the three improvisers operated with methodologies employed by the League: personal set-ups, no pre-existing plans, and an embrace of how each other’s actions and data would influence their own outputs. There is something to it that John Bischoff’s closing act in a concert celebrating his career is not a solo or even some kind of spotlight-hogging concerto-like work. Instead, he blurred into the group, as if a part of one of his hero David Tudor’s combines, working collaboratively with Perkis and Fei.

In some ways, Bischoff’s precision in the first half made adjusting to the looser structures and more generalized sounds of this League-inspired improvisation harder for a moment. In reviewing some recordings of the League after the performance, it was especially clear how much they had captured its rambunctious, live musicality.

This concert, especially after being rescheduled from its 2020 date due to the Covid-19 pandemic, had an extra layer of significance with the announcement that Mills College was going to close or change status in some way. In the months that have followed that night in April 2021, Northeastern University and Mills have created a plan to merge. Although much has yet to be clarified about the future of Mills College’s educational missions in the wake of its new relationship with Northeastern, Bischoff’s retirement is part of a generational chapter’s close for the college, following the retirements of longtime CCM co-directors Maggi Payne and Chris Brown, and other faculty from the music department including Roscoe Mitchell and Fred Frith. Mills has experienced considerable shifts of musical trajectory before but has found new ways after the departures of previous faculty such as Darius Milhaud, Luciano Berio, Alvin Curran, Pauline Oliveros, and Robert Ashley. It has also invested in new possibilities such as when the San Francisco Tape Music Center became part of the college, later renamed the Center for Contemporary Music.

Amongst the current students and alumnae of the college, there is still a great deal of concern about what will, or will not, survive into the partnership with Northeastern. The unique music opportunities at Mills are worth supporting, as is finding ways to shine a light on the historically significant events and people throughout the music department’s history. Most importantly, I hope Mills in every potential iteration it may be transformed into, is one that continues to support women and women’s educational spaces.