This concert took place 4 March 2020 at the Krannert Center for the Performing Arts, Stage 5, on the campus of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Illinois, USA. For more information visit: https://www.nonopera.org/WP2/hpschd-50/

Reviewed by Ralph Lewis

Champaign, Illinois, USA

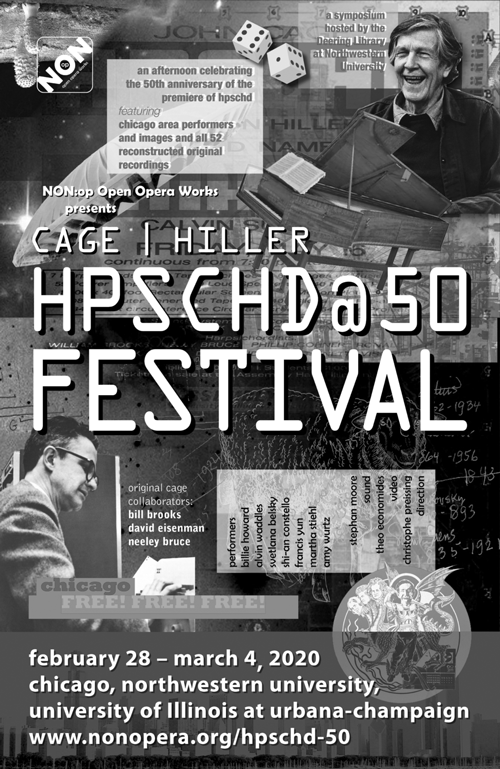

Fifty years after the premiere of John Cage’s immersive, multimedia work HPSCHD at the University of Illinois, it returned to Champaign-Urbana in a performance by Chicago-based NON:op Open Opera Works in collaboration with the Illinois Modern Ensemble. The production, HPSCHD@50, was led by Christophe Preissing with input from William Brooks and Neely Bruce, two of the seven harpsichordists from the 1969 premiere. This anniversary concert on March 4th, 2020 followed NON:op’s performances of HPSCHD a few weeks earlier at The Chicago Cultural Center, a symposium about the work at Northwestern University, and a panel discussion the day before at the University of Illinois’s weekly composition forum.

Fifty years after the premiere of John Cage’s immersive, multimedia work HPSCHD at the University of Illinois, it returned to Champaign-Urbana in a performance by Chicago-based NON:op Open Opera Works in collaboration with the Illinois Modern Ensemble. The production, HPSCHD@50, was led by Christophe Preissing with input from William Brooks and Neely Bruce, two of the seven harpsichordists from the 1969 premiere. This anniversary concert on March 4th, 2020 followed NON:op’s performances of HPSCHD a few weeks earlier at The Chicago Cultural Center, a symposium about the work at Northwestern University, and a panel discussion the day before at the University of Illinois’s weekly composition forum.

HPSCHD’s premiere on May 16, 1969 represented a culmination of two years of collaborative efforts between John Cage and the university’s Experimental Music Studios founder Lejaren Hiller. Laetitia Snow, James Cuomo, James Grant Stroud, and Max Mathews also contributed in realizing the work, which required extensive computer programming and technological expertise. Initially envisioning a work based on a commission from Swiss harpsichordist Antoinette Vischer, Cage would find procedural inspiration in Mozart’s dice-based composition game. As one of a handful of proposals he made to the university’s Center for Advanced Study, this starting point of combining harpsichord solo with electronic music that used dice roll-based chance operations eventually expanded into an arena-sized happening in the university’s 18,000 seat Assembly Hall (now State Farm Center).

At its premiere in 1969, seven amplified harpsichordists played aleatoric parts constructed from original material, and music from Mozart and other historical composers using FORTRAN computer code that replicated and built upon the dice rolling procedures. The additional media used, according to Kenneth Silverman’s biography of Cage, included 52 monaural tape machines playing 208 different tapes through 59 speakers, 64 slide projectors showing 6400 slides, and 40 films projected on eleven 100 x 400 film screens as well as a 40 foot circular screen. As if to further pinpoint the work’s moment in time, many of the slides contained newly released images from NASA’s space missions, anticipating the moon landing a few months later in 1969.

While HPSCHD is known for the multifaceted spectacle of its premiere, the resources required to stage it are as open-ended as many of Cage’s other compositions. As described on the John Cage Trust’s website, HPSCHD can be staged with one to seven harpsichordists and at least two speakers playing some of the many tape parts. Similarly, its duration can be any agreed upon amount of time. In this way, HPSCHD resembles other indeterminate works by Cage, where another staging can bring about profoundly different results.

Even so, the premiere’s staging and ambience seems to create a peculiar sense of continuity in how HPSCHD is performed, even if the scale of these later realizations is noticeably smaller. The impact of this is similarly visible in tributes to the work. For example, a commemorative concert party on May 16, 2019 (the actual 50th anniversary of HPSCHD’s premiere) at Analog, a wine bar in Urbana, Illinois, presented an array of music and art by local artists approximating the premiere’s ambience.

Another amusing aspect of this continuity is the presence of David Eisenman at the 1969 premiere, the 2019 Analog concert/party, the panel in Chicago, at this 50th anniversary performance, and other HPSCHD-related events. In addition to being in touch with Cage as part of planning the premiere (a telegram from 1968 sent to him by Cage regarding the planning, that David Tudor is likely to play Variations II on campus that year, and a suggestion about aerial balloon popping to celebrate Mardi Gras is among documents collected about it), he made and vended the famous T-shirts depicting Cage’s head on Beethoven’s body at the premiere. He has remained a presence, with more T-shirts, buttons, and CDs ready to share at each event. Ever the puckish figure, each encounter with Eisenman furthers my fascination with the premiere.

Joel Chadabe, who has produced several presentations of HPSCHD since its premiere and was a resource to Preissing and NON:op Open Opera Works, has similar thoughts about the ambience of the work. Writing about the general performance history of HPSCHD on his personal website, which he continues to update (already listing this March 4, 2020 performance at the time of writing), he shares these thoughts: “HPSCHD, in my view, should always be extravagant, exuberant, and wild. Unlike a sewing machine. I understand it and hear it as a joyful melee of continually sustained intensity, of computer-generated trumpets sounding an ongoing charge by a cavalry of amplified harpsichords through a landscape filled with thousands of flashing and swirling overlaid projections of color, form, and space imagery on the ceilings and walls and, as on occasion, on special screens placed throughout the space.“

The recent performance at the University of Illinois’s Krannert Center for the Performing Arts took place on Stage 5, the intimate concert space and bar in the middle of the building’s immense lobby. Four harpsichords were arranged on the stage by the bar, and within the seating area. Its personnel included harpsichordists Francis Yun, Shi-an Costello, Mathal Stiehl, and Ann Warde, audio by Hugh Sato, visuals by Theo Economides and Ilse Miller. Mark Enslin and John Toenjes provided additional support.

The work’s electronic music elements appeared in ways that reflected a more nimble approach geared toward presenting HPSCHD in different spaces, as well as contemporary trends such as the use of smart devices in performances. Rather than tape machines (or any of their contemporary equivalents) and speakers, attendees’ phones played the electronic music parts. The event program asked attendees to call the specified phone number and select a number between 1 and 52. Based on their choice, one of the original tape parts would begin playing from their phone speaker. As of July 8, 2020, the telephone number (217-290-2473) is still active and Preissing has approved sharing the number here. One of the joys in writing this review was calling to check if it was still active, sometimes multiple times a week.

In a similar way that the audience’s phones replicated the multiple tape players and speakers, a more lithe, mobile approach was also used to reference the projected images. A few people circulated throughout the crowd with iPads showing photographs of space, in a nod to the NASA photos, and projections from the premiere. While less ambitious and certainly less impactful than Calvin Sumsion’s 1969 visual spectacle or this performance’s use of phones as speakers, the presence of photos of nebulae and constellations as people walked by increasingly felt like a part of the space’s casual mass of the harpsichords playing and cell phones creaking and popping electronic music throughout. It seems that the imagery is less important than the environment-distorting presence of projections and light sources, to capture the feelings Chadabe described. (Notably, the performances at Chicago Cultural Center’s Preston Bradley Hall used extensive screens that NON:op Open Opera Works hand-built for the occasion).

In thinking about the Krannert Center as a space, I was reminded that where this concert was held, celebrated its own fiftieth year anniversary recently. Opening in April 1969, the Krannert Center would seem to be a likely partner with HPSCHD, especially considering its current stature in presenting music and dance events in Champaign-Urbana and its close proximity to the university’s music building. Even so, HPSCHD’s premiere in 1969’s size and focus on simultaneities throughout a single large space made the assembly hall a much better fit for it.

On the other hand, this year’s event reflects the presence Krannert has established in the Champaign-Urbana area. In addition to being the performance hub for music, theater, and dance productions, its main lobby was designed to be a meeting place in which people attending different productions could meet. The stage in the central part of the lobby used for HPSCHD has had as many pre-concert talks and post-concert libation partaking, as it has had performances of its own. It makes sense that one of the most attention-getting works from the University of Illinois this side of Salvatore Martirano’s L’s GA should finally appear in its marquee performance space. Even so, the question is, how did it engage its attendees?

Of the 50 people who came, including those from the preceding Illinois Modern Ensemble Concert in the Studio Theater, a number stayed as HPSCHD played on until Martha Stiehl’s final notes. Many, including UIUC School of Music Senior Recording Engineer Frank Horger, were engaged by it. Horger related that “HPSCHD was pleasantly disjointed, easily digestible, and fascinating for both its musical content as well as its historical context. It welcomed spectators to linger and focus on the disparate elements both individually and collectively as part of this 'happening'.”

History doctoral student Kat Wisnosky, meanwhile, had another take. “My first thought about it was that it didn't quite work as well as the organizers hoped. People seemed shy about participating.” Wisnosky went on to suggest that “maybe having started it in the theater space and then moving it out into a larger area would have worked better. The concept and how they were trying to do it was really interesting. I just don't think the audience was into it.” While Wisnosky’s comments do reflect on the relative energy of an audience for a Wednesday evening concert as compared to a massive happening on a Friday or Saturday, they also reflect, perhaps, on how times have changed as have cultural interaction with Cage.

Although experimentalism has continued on since Cage’s passing, and is not simply the domain of the New York School aesthetics, what Cage’s work is and how it is dealt with, even in historically receptive spaces is overdue for evaluation. On a personal level, having in the last decade seen how Cage is digested quite differently in various contemporary music spaces throughout the U.S.A., often there is a confusion, a disinterest, or sense that Cage overshadows other experimentalism. While encouraging people who have not yet performed Cage’s music or gotten over acceptable, initial giggles to venture further, it is a good sign that other experimentalist approaches and voices are being amplified too, such as in Jennie Gottschalk’s superb book Experimentalism Since 1970.

Disconnects with HPSCHD also speak to the relative trouble in explaining historical or older works that depend upon a community to sustain new or related event-going practices. It should be easy - HPSCHD’s atmosphere is so close to where Burning Man, arena rock shows, dance clubs, and immersive art environments have gone to since. But being pitched to a concert-going crowd, it feels different. Cage scholar Sara Haefeli, also a panel member for the 50th anniversary celebrations, writes about how place and time feel different in her article “HPSCHD, Gesamtkunstwerk, and Utopia.” Even in this seemingly now-familiar space where we can converse, drink, and tinker with our smart devices this “utopian ‘no place’ and…’no time’ suggest that HPSCHD represents a possible, anarchic future, and not a prescriptive future; the Utopian future is not a fixed, determined “should be,” but rather a flexible, multiple ‘what if.’”

I deeply enjoyed this “no place” and had a great “no time” during the performance. While, indeed, some people were shy about things, they also were intently watching the harpsichordists play, often dialing up Cage’s monaural parts with one hand and enjoying a beverage in the other. Others sat and chatted. Newcomers and longtime tenured professors alike bought and donned David Eisenman’s Cage-headed Beethoven T-shirts. Attendees walked onto and over the small stage to look inside the harpsichords and at the sheet music. James Beauchamp, Scott A. Wyatt, Sever Tipei, and Eli Fieldsteel, Hiller’s successors in the University of Illinois’s Experimental Music Studios and Computer Music Project, were all in attendance.

The harpsichordists played their parts exquisitely. After spending time watching Francis Yun and Shi-an Costello play up close, I made my way to Ann Warde’s harpsichord, who was, at that moment, surrounded by a number of cell phones playing the electronics tracks, creating a poignant and complex texture. As the performance winded down, I settled in and followed along with Mathal Stiehl’s part. While this “do it yourself” performance (as described by HPSCHD@50 themselves) was intentionally not extravagant, the cranky, spirited performance was my favorite Wednesday night of 2020.

In follow up correspondence with Preissing he spoke about the experiences he and his collaborators went through to produce this set of performances. Even in attempting to make this University of Illinois version of HPSCHD a “no projectors, no screens, no hassle” performance, the amount of behind the scenes work was difficult. It included tracking down the individual 52 electronic music tapes, their digital versions, setting up the app to control them, and locating enough harpsichords for each performance.

While the last performance of the HPSCHD@50 Festival was postponed due to COVID-19, this Champaign-Urbana performance and the events in Chicago show the kind of care and excitement Cage’s music still inspires in people. I am curious if and how people will stage it in 2044 and 2069. Perhaps augmented reality goggles simulating some aspects of the enormous crowds of the original? Perhaps it will be exponentially harder to find a three-dimensional harpsichord? Will there be a new musical space that Champaign-Urbana’s music community uses and how will HPSCHD fit into it? Maybe a future staging will take all evening? Maybe all of the harpsichordists will be on the screens and the electronics will be reconfigured using AI for each performance? Maybe it will stretch for 100 hours to celebrate 100 years of HPSCHD? One thing is for certain – this piece will live on in some form for a very long time.