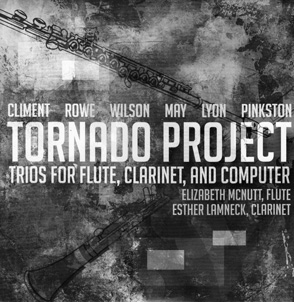

Compact disc, 2016, Ravello Records, RR7908; available from Ravello Records, LLC, 223 Lafayette Road, North Hampton, NH, USA; telephone: +1-603-758-1718; www.ravellorecords.com.

Reviewed by Ross Feller

Gambier, Ohio, USA

The Tornado Project, conceived of by composers Ricardo Climent and Paul Wilson is a platform to commission works for flutist Elizabeth McNutt, clarinetist Esther Lamneck, and computer-generated sound. Their recent compact disc of trios released on Ravello Records features compositions by Climent, Wilson, Robert Rowe, Andrew May, Eric Lyon, and Russell Pinkston, several of which are well-known names in the academic, computer music community. This collection contains a variety of aesthetic and technical approaches to making electroacoustic music, state of the art recordings and compelling performances and compositions. In addition to the cd itself there is a dedicated website with additional album content containing information and materials about each piece, including scores and program notes. Having the scores easily accessible in pdf format helps to understand much about the work and compositional motivations that might not be immediately obvious to the ear. It is assumed of course that one is able to read the notation, which seems reasonable to expect of a listener who enjoys listening to advanced tokens of computer and electroacoustic music.

The Tornado Project, conceived of by composers Ricardo Climent and Paul Wilson is a platform to commission works for flutist Elizabeth McNutt, clarinetist Esther Lamneck, and computer-generated sound. Their recent compact disc of trios released on Ravello Records features compositions by Climent, Wilson, Robert Rowe, Andrew May, Eric Lyon, and Russell Pinkston, several of which are well-known names in the academic, computer music community. This collection contains a variety of aesthetic and technical approaches to making electroacoustic music, state of the art recordings and compelling performances and compositions. In addition to the cd itself there is a dedicated website with additional album content containing information and materials about each piece, including scores and program notes. Having the scores easily accessible in pdf format helps to understand much about the work and compositional motivations that might not be immediately obvious to the ear. It is assumed of course that one is able to read the notation, which seems reasonable to expect of a listener who enjoys listening to advanced tokens of computer and electroacoustic music.

The first piece on this disc, Russian Disco, begins with a heavy dose of chaos, somewhat unexpected given the title, which would imply a regular, recurring beat pattern in four or two, perhaps along with a dated sounding analog synth patch from the late 1970s. In Climent’s program notes we read that he has “always been fascinated by the fact that, out of broken tiles arranged within architectonic contours such as frescoes and curved stone benches, artists could provide a sense of organic growth to inert materials, without necessarily being too logical or consistent. Ultimately, this idea and the joy of working with the best performers, informed my compositional thinking when writing Russian Disco.” The title was taken from a homonymously titled book written by Vladimir Kaminer about the nightlife in Berlin from the point of view of a Russian immigrant.

This piece is conceptually challenging and utopian in several respects. The composer has integrated the idea of a sushi delivery system to mount and project various parts of his score. The score itself is not a stable entity but instead offers the performers structural pathways, which they explore using improvisational decision making procedures. On the website for this disc, Climent includes an extensive notational key, detailed instructions for performance, and a meticulously notated sample score of one possible realization.

Throughout the piece we hear standard expressions from the twentieth-century woodwind repertoire, including breath sounds, key clicks, and various tonguing effects. Many of these extended techniques are matched, enhanced, or instigated in the computer part. Examples include breath sounds matched with similar timbres having shaped reverb ‘tails’, and key clicks and rapid tonguing enhanced with percussive, granular synthesis tremolos. In addition to these, we hear an unusual mixture of frisky, playful gestures with what are essentially angular, atonal materials.

About a third of the way into the piece the expansion and exploration of registral space takes on a sudden, dramatic, downward extension (perhaps the hand has dropped a chosen piece of sushi onto one’s plate?). The effect would be akin to a pedal point if the piece had been composed with functional tonality in mind.

At the two-thirds point we hear more surprises: shouting and vocal exclamations that are both unexpected, since there are no obvious vocal sounds before this point, and somewhat expected, as many of the previous outbursts could have easily included vocal sounds. In fact these outbursts include characteristics of vocal expression, such as glissandi, sharp, percussive attacks, and pitch registers of the human voice.

The computer part for this piece compliments the flute and clarinet parts, while providing them with extended resonance and space. The composer uses the computer more for processing than as a stand-alone, foreground part.

Climent has resurrected a fascinating approach to score making and conceiving of a composition as an event with permeable boundaries and many plausible routes. Add to these two virtuoso performers, a kitchen sink of extended techniques, and a pre-composed digital audio file and you have one composer’s recipe for radical innovation.

Robert Rowe’s Primary Colors features freely tonal and lyrical, acoustic materials combined with sophisticated computer processing techniques. In the terse program notes for this piece the composer states that the title refers to “a recognition that the piece is composed of a number of highly differentiated and internally consistent blocks of material.”

After a short introduction featuring repeated tones played by the flute and clarinet parts one hears them echoed by the computer and spatially and dynamically distributed. They sound ‘distant’, which imparts a sense that they are employed as processors of the live parts, which are themselves heard centered, up front, and with little processing applied.

The computer part was produced from the composer’s software program written in C++. Essentially it ‘plays’ prepared audio files, combines the sounds from the woodwinds, and processes and adds effects to all the sounds. The composer has marked off 36 “states” in the score that occur after various amounts of measures. One assumes that each state contains instructions for specific processing techniques to be employed and initiated at the moment when a state changes to its successor.

Among the computer processing techniques that are evident to the ear include: harmonization, ring modulation, delay, flanging, and echo. At times, especially in combination, they create an ethereal, otherworldly quality, which contrasts nicely with the groundedness of the live instruments. Also, the composer’s use of echo and flanging create the illusion, like the chorus effect, that more than two instruments are playing at a given moment.

Primary Colors literally ends with a bang, an event that serves to bring things to an abrupt close. The materials heard immediately prior to this imply continuation and extension, so the bang tells us that the piece could have gone on for minutes more but the composer has intentionally not done so. Similarly, in Rowe’s program notes, he provides only what is essential.

When I first saw the title for the next piece by Paul Wilson I asked myself: what is it that is beneath the surface? And how will I know when I encounter it? The composer’s goal when writing Beneath the Surface was to “address the issue of composing a piece that uses extremely quiet sounds.” His solution was to employ a restricted sound world that develops from the woodwinds’ whispers and key clicks, in order to create intimacy. “The composition explores the tensions between noise or air sounds and pitch, and the onset of vibrations both within and between the instrumental and computer parts.”

This piece is chock-full of subtle sounds and flourishes such as breath tones, key clicks, flutter tonguing, tremolos, and trills. The flute and clarinet receive equal focus, and for much of the piece occupy the same registral space, a blend that makes it difficult to tell them apart.

Beneath the Surface begins with reiterated key clicks, fast tremolos, and erratic rhythmic gestures. Gradually breath tones and high frequency squeals enter along with a percussive, granular computer background. This texture also contains echoes and a heavy dose of reverb.

Toward the middle of the piece we hear agitated, multiphonics and a series of sustains that slowly change with respect to pitch and loudness. The live parts become even more agitated, set against the computer backdrop of sustained resonance. After a series of flourishes we hear mildly harsh difference tones. All told, this was a captivating texture.

About two minutes from the end it sounds as if the piece is fading out. However, it comes back, growing in intensity, as the flute and clarinet play scalar materials until the actual end. By that moment all that is left are the initial note attacks and noise contents.

Still Angry, the title for Andrew May’s dynamic composition, represents a piece that presents a metaphorical and sonic battle between avant-garde improvisation and the 1970s Manchester scene bands. The title conjures up the notion of a grudge, or unpleasant event, that refuses to recede into the past, something unresolved and perhaps unresolvable.

According to the composer’s liner notes, “Still Angry is a double concerto: a struggle between the instrumentalists, who are set on doing avant-garde improvisation, and the computer, equally determined to do songs by 1970s Manchester bands.” The instrumentalists perform indeterminate and improvised materials, represented graphically in the score, while the computer ‘plays’ samples of songs by Joy Division, and quotations ‘covered’ by the composer of songs by Joy Division, Magazine, and the Buzzcocks.

This piece begins with a stock four count on a hi-hat sound, followed by a texture featuring sustains in both the live instruments and the computer part. Gradually this changes to a rock texture in which we hear a distorted guitar or bass guitar, and drum set. Here also the wind players play a high frequency dyad that sounds like a distorted guitar. Immediately prior to this we hear a female voice (played by the computer) stuttering and asking “is this at all interesting?” In the context of this piece, this question can be thought of from the perspective of each ‘side’ in the battle between avant-garde improvisation and 1970s Manchester rock.

The next section contains chaotic, thick textures with plenty of reverb, and multiphonics, shrill register pitches, and distorted guitar sounds. This all leads to a free-for-all in which a stock rock beat occurs, contrasted with screaming winds, and mixed in such a way that all parts are equally present. This texture, and several more like it, is so harsh that it physically hurts to listen to it, at least with headphones. The battle May describes has intended and unintended consequences, fallout, or collateral damage.

The battle between the computer and instrumentalists is poignant and well articulated. May connects the sense of unquenchable anger to various outrages, from unjust wars to ill-fitting clothes. At the end of his program notes he writes, “The stylistic chauvinism that makes music divide people instead of uniting them is probably not the best one – but I’m still angry about it.” As many scholars have shown, music is often used as a marker and regulator of groups and group dynamics. In order to be coherent as separate entities groups cater to exclusionary measures, but this is different from saying that the root cause is stylistic chauvinism.

It is an open question whether the composer equates pop music as found in the 1970s Manchester scene bands with stylistic chauvinism, or believes that “avant-garde improvisation” is maintained by stylistic chauvinism? Still Angry would seem to leave this question unanswered. The composer’s status in academia argues for the avant-garde side. Yet, May also apparently plays, or played in a band that covered Joy Division.

Eric Lyon’s title, Trio for Flute, Clarinet, and Computer implies a certain formality cast within a new context, with the computer taking the part formerly reserved for the piano. However, it also implies a trio of equally important parts. According to the program notes, the computer part is wholly based upon sounds made by the flute and clarinet, captured live during performance. Since Lyon decided not to amplify the woodwinds he sought to balance the three parts by intentionally making the computer part match the winds, effectively turning the computer into a kind of acoustic instrument.

The piece begins with each instrument finishing the ‘thought’ of the other. Lyon creates a virtual space by placing the clarinet panned hard right, and the flute panned hard left. They play in an unstable, quasi-heterophonic manner wherein each instrument changes speed by way of different tuplet values. These carefully crated, gestural materials lead to a remarkable distorted glissando sound. With the help of extended delay times, the composer changes the decay rates in order to produce more descending glissandi, alongside a kind of sample and hold approach.

This piece unabashedly partakes in surface exploration, supported or girded by a simple formal structure. The formal structure is marked by static, sustained timbral sections, featuring the aforementioned descending glissandi, followed by quasi-heterophonic material that veers off course in a variety of ways (e.g., the descending glissandi). The live parts often have unison parts that become rhythmically out of sync, but in more chaotic and unpredictable ways than say, Steve Reich’s infamous phasing technique. This formal plan remains intact, more or less, until the very end of the piece.

Lyon’s programming prowess is in evidence throughout the piece. The computer part contains a potpourri of sampling and processing techniques including harmonization, pitch bends, convolution, sample and play and sample and reverse, and reverb gating. In the score, the computer part indicates when and how to activate the live sampling process and which location to copy the samples. These samples have several compositional purposes. When sounded with the live instruments they act as resonance boosters, which give the instruments more presence. They also help to localize the instruments in a virtual space. Occasionally Lyon playfully switches the virtual and ‘real’ instruments or the flute and clarinet parts and their sampled echoes. What is most intriguing about this piece is that the composer probes a kind of instrumental virtuality that is well blended and ‘realistic’, but is unafraid to stand out as ‘artificial’.

In the program notes for Russell Pinkston’s e++, he states that he wanted to take advantage of the performers’ musical virtuosity as well as their “colorful personalities and remarkable stage presence.” Apparently, their preferred stage set-up is to stand far apart “facing each other from opposite sides of the stage.” This spatial arrangement led the composer to look “for opportunities to let the two of them interact with and play off each other, as well as with the computer.” He continues: “I also made sure that there was a section where these two highly innovative performers could improvise using extended techniques, making sounds on their instruments that very few others can make.”

This piece features whimsical ‘conversations’ between the two wind players, and between them and the computer. The score is full of performance indications such as: very expressive and somewhat mischievous, cheeky, surprised, intrigued, interested, teasing, slightly provocative, etc. These indications effectively coax the performers into enlivening various musical fragments, in specific ways.

The piece is interactive in several respects. The computer part is instructed to trigger things after waiting for the instruments to play certain pitches in certain measures. The instrumentalists are sometimes asked to match aspects of the computer sound, such as an echo. The composer has also clearly composed similar, echoing, and hocketing parts that suggest instrumental interaction. Finally, the composer interacts with the performers with his provocative performance indications.

Pinkston’s music often utilizes live capture to “create a rhythmic groove backdrop” as one online reviewer put it. This groove is first heard via a low frequency bass sound that timbrally resembles a cross pollination between a hybrid flute or clarinet, and the Australian didgeridoo. The composer has grafted rhythms that one might hear an upright bass play in a traditional jazz context, onto this groove.

At the beginning of e++ the clarinet plays material marked “Very expressive and somewhat mischievous. This musical comportment is characterized by sustains and staccato notes, unstable, changing dynamic levels, and unpredictable, tuplet-laden rhythms. Heard as a whole, one is reminded of passages in Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Harlequin for solo clarinet, and certain clarinet passages in Igor Stravinsky’s Petrushka. It is as if Pinkston is referencing musical signs of a puppet and commedia dell’arte character.

In the next section, the computer begins to closely echo the clarinet part, creating a quasi-minimalist texture in which joins the flute, instructed to play in a “Teasing, slightly provocative” manner. This leads to the extended techniques improvisation section, heard as an interruption or disruption of the previously composed materials. Gradually these materials are captured and granulated by the computer, serving to both prolong and increase the sense of instability inherent in the gestures and very concept for this section. From here, the chaotic rhythms gradually coalesce into a regular, recurring pattern of 16th notes. The didgeridoo bass reappears marking the downbeats of each measure in 4/4 time, and the flute and clarinet begin to play stock patterns of 16th and 8th notes, which are indicated to be performed “Brightly, cheerfully” with a “normal tone.” Given the previous sections’ materials, the clearly tongue-in-cheek performance indications here, and the chromatic pitch collections used, would seem to indicate a humorous pastiche rather than a straightforward ‘groove’ reference.

The next section is conceptually ‘darker’, featuring the winds trading triplet patterns over an intriguing granulated computer part, serving as a timbral backdrop, or pedal, that carries through until the end of the piece.

This is a wonderful collection that contains a diverse array of computer music compositions by some composers who are well known as composers but also for writing software and externals. It reminds us all that there is a good reason why some composers resort to coding, namely: to compose vital and intriguing music and realize the worthy ambition to create new contexts for sound. Given the current prevalence of pieces with acoustic instruments and computer-generated sound parts, the ‘trio’ heard on this recording represents a new standard, chamber ensemble. Lastly, with any work that includes indeterminate elements or improvisation, the performers will make a huge difference in the heard result. In this sense Elizabeth McNutt and Esther Lamneck have put together some masterful and creative performances here, which is to be expected from instrumentalists of their world-class caliber.