Compact disc, 2012, innova 838; available from innova Recordings, ACF, 332 Minnesota Street #E-145, St. Paul, Minnesota 55101, USA; telephone: (651) 251-2823; electronic mail innova@composersforum.org; http://www.innova.mu/.

Reviewed by Jonathan Brown

Riga, Latvia

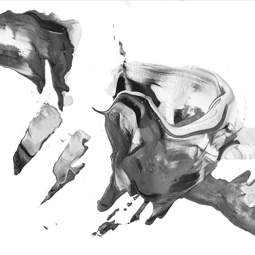

That Alexander Berne is described equally as composer, multi-instrumentalist, and visual artist is an essential prerequisite to his most recent release, Self Referentials Vol. 1&2 An Unnamed Diary of Places I Went Alone. As all good CD cover artwork ought, Berne’s hand-rendered painting does much to foreshadow the music. Just as the accompanying artwork’s colors seem to emerge organically and drift from the paper, so too do the colors, textures, and timbres of the music. The painting’s smooth, nearly effortless brush strokes, dissonant color relationships, and empty space, are all obligatory indicators of the music’s mysterious and enigmatic character, too.

That Alexander Berne is described equally as composer, multi-instrumentalist, and visual artist is an essential prerequisite to his most recent release, Self Referentials Vol. 1&2 An Unnamed Diary of Places I Went Alone. As all good CD cover artwork ought, Berne’s hand-rendered painting does much to foreshadow the music. Just as the accompanying artwork’s colors seem to emerge organically and drift from the paper, so too do the colors, textures, and timbres of the music. The painting’s smooth, nearly effortless brush strokes, dissonant color relationships, and empty space, are all obligatory indicators of the music’s mysterious and enigmatic character, too.

As his variable and multiple ambitions suggest, Berne is uniquely prolific. Where many artists might toil over a single work for years at a time, Self Referentials is Berne’s third offering in as many years (and this is only to count his musical achievements). This most recent two-disc dispatch is preceded by the three-disc Composed and Performed by Alexander Berne, followed only one year later by another double disc: Flickers Of Mime/Death of Memes. What’s more, The Abandoned Orchestra, co-credited with the achievements of these releases is only a humbling pseudonym for Berne himself.

Berne’s label, innova Recordings, attempts to characterize Self Referentials with genre classifications encompassing “world,” “experimental,” and “new music,” in the categories of “ambient,” “music for dance,” and “soundtrack.” But all miss the mark. Any listener will identify with these associations, perhaps hearing how this music could fit any one of these moulds momentarily. Ultimately, the music weaves over and above these distinctions, carving out a unique space for itself. If anything, Self Referentials is a potent reminder of how genre distinctions have become increasingly problematic.

Yet, it is exactly this conglomeration of influences that characterizes the entire work. But these influences are better realized biographically than in terms of genre. That wind instruments, and saxophones specifically, were Berne’s introduction to music is ubiquitous throughout Self Referentials (winds comprise the music’s most fragile and graceful textures, while also serving as its foundation). The fact that jazz served as Berne’s entryway into music as a young musician in New York is audible throughout. Berne has been described as an innovator in the realm of wind instruments. This explains the music’s wealth and depth of timbres (he’s credited with designing the saduk, an instrument resembling both the saxophone and the Armenian duduk).

Self Referentials, Volume 1 is comprised of twelve tracks, the first nine of which range from two to nearly six minutes in length. These precede Sonum Onscurum: Headphonic Apparitions Part I (the first of three parts). Disc two contains seventeen shorter tracks (the longest is exactly four minutes) that are all are titled, or more accurately, distinguished with the Roman numerals: I–XVII.

Threnodic Winds from the first disc, is an inescapable nod to Krzysztof Penderecki in, at least, the track’s titling. But what this title infers beyond the music’s gradual, mysterious, and haunting swelling seems superfluous. Ruse (Fantastique) explores the collection’s capacity to simultaneously host disparate timbres and rhythmic depictions. Fugal Melancholia is one of the most distinctive tracks on the first disc, especially since it is the only purely instrumental and unaccompanied music.

The titling of the initial nine tracks seems to detract from the inherent, suggestive capacity of the music. Why these tracks are not awarded the same ambiguity of the second disc is not clear. In fact, with the exception of disc two’s subtitle, An Unnamed Diary of Places I Went Alone, which strikes an unobtrusive balance between pointed description and inviting ambiguity, the music speaks sufficiently for itself. This is reflected in Maxwell Chandler’s liner notes, which could be equally characterised as prose. The final line of Chandler’s notes, which promotes its own literary quality, reads: “These are not liner notes, these are the liner notes.” This suggests that although his words are placed where liner notes usually are found, they serve a greater descriptive and accompanying role than that normally attributed to liner notes.

In his introduction he writes: “Like daydreams or memories, good works of art regardless of medium offer an inner landscape for the audience to traverse, the work serving as the terra firma … Alexander’s Self Referentials is indicative of the type of work which facilities a compulsion to take such an inner journey again and again.”

Yet, there is little that is “terra firma” in Self Referentials. Sinewy phrases in the winds and prolonged fragile breaths underpin the work, though they simultaneously communicate the work’s longer forms, intuitive narrative, and the sense of “journey” mentioned in Chandler’s notes. But to contrast, the listening experience of Self Referentials is equally fractured. This percussive and dramatic fragmenting arises in oscillating musical material, appearing and reappearing in imitations of itself throughout both volumes. In fact, the inherent beat or percussion of Self Referentials is often “exformed” – simultaneously removed from, but evoked by the music’s constant droning and subtle pulsating.

The way in which recognizable or distinctive musical ideas (be they timbres, textures, or gestures) recur and reappear throughout Self Referentials is comparable to a pungent déjà vu. Ideas repeat like nostalgic reminiscences, vague recollections, or daydreams. When they reappear, they do so as paling reflections of the original statement, altered and informed by the oscillating experience of the music’s narrative.

However, what is ultimately striking about Self Referentials is the impact of the narrative arch reaching across individual tracks from both discs. This narrative is distinctive despite the many ways Berne fractures the immediate listening experience. In realizing this narrative, this journey, Chandler’s liner notes correctly point to Berne’s music as both “the landscape to be explored, and the Sherpa that accompanies you on the journey.” The music is as enigmatic and mysterious as it is inviting.

Where, undoubtedly, the music is most successful is in integrating its instrumental components with synthesisers and samples. The seamlessness of the transitions between these indistinguishable timbres catalyzes much of the music’s mysterious, but inviting qualities. Moreover, Self Referentials is at its most powerful in its quieter moments – when the winds have the space and platform to perform the full longevity of their overlapping phrases.