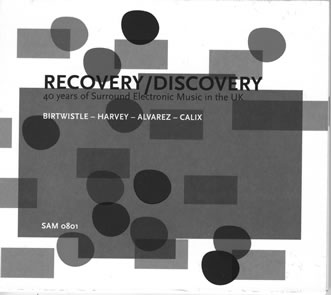

Various: Recovery/Discovery—40 Years of Surround Electronic Music in the UK

DVD-Video/CD-Audio, 2008, SAM 0801; available from Sound and Music, 3rd Floor, South Wing, Somerset House, London WC2R 1LA, UK; telephone (+44) 20-7759-1800; electronic mail info@soundandmusic.org; Web www.soundandmusic.org/resources/publications/RecoveryDiscovery.

Reviewed by James Harley

Kitchener, Ontario, Canada

Sound and Music (SAM) came about as a cooperative venture involving four important British new music organizations: British Music Information Centre; Contemporary Music Network; Society for the Promotion of New Music; and Sonic Arts Network. The SAM Web site presents a vision statement that could be the envy of all new music organizations:

Sound and Music (SAM) came about as a cooperative venture involving four important British new music organizations: British Music Information Centre; Contemporary Music Network; Society for the Promotion of New Music; and Sonic Arts Network. The SAM Web site presents a vision statement that could be the envy of all new music organizations:

Our vision is a world where new music and sound transforms lives, challenges expectations, and which celebrates the work of its creators. To achieve that goal, we champion innovation, learning, and artistry through: exploring contemporary approaches to music and sound creation; deepening engagement with a high quality program embracing live events, new technologies, and participation; optimizing the impact of our work by raising its profile, developing audiences, and cultivating partnerships.

One aspect of SAM’s work is publication, and its first release is a disc that combines important historical electroacoustic works with newer ones. This release also aims to highlight the importance of spatialization in electronic music. The introductory note by producer Lieven Bertels outlines the history of spatialization techniques, going back to Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Gesang der Jünglinge. The DVD format enables spatialization to be encoded for home listening, and all the works on this disc are mixed to be heard as four-channel pieces (one, was mixed for 4.1, four channels with an additional signal intended for the sub-woofer). The dual-sided side includes stereo mixes on the other side, for playback on compact disc players where a surround-sound system is not available.

The main historical impetus for this release was the “rediscovery” of Chronometer, a four-channel electroacoustic work by Harrison Birtwistle, premiered in London in 1972. Mr. Birtwistle, now considered one of the most important living British composers, has produced very few electroacoustic works (his opera The Mask of Orpheus, from 1984, includes a substantial electronic element, produced in collaboration with electroacoustic composer Barry Anderson, who completed the work at the Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique —IRCAM in Paris). For that reason alone, the work is of historic interest, but it is also notable for the spatialization (an element Mr. Birtwistle has explored quite extensively in his instrumental works as well), and also for the obscurity the work has enjoyed for most of its existence. For Chronometer, Mr Birtwistle worked closely with Peter Zinovieff, an important figure in the history of electronic music, known, among other accomplishments, for EMS Putney Studio, his company that developed analog synthesizers such as the VCS3, popularized by Pink Floyd and others.

Chronometer was released in a stereo version on a 1975 LP that included a major orchestral work by Mr. Birtwistle from the same year as Chronometer, The Triumph of Time, featuring Pierre Boulez conducting the BBC Symphony Orchestra (Mr. Boulez was Principal Conductor there, 1971-1975). At just under 25 minutes, Chronometer is a substantial work. According to Mr. Zinovieff, who is credited with “realizing” the tape, the sonic material was derived from recordings of two clock mechanisms: Big Ben, at Westminster, one of the most famous clocks in the world; and the Wells clock at the British Science Museum, one of the oldest surviving clocks, apparently running continuously since 1392. Ultimately, something like 100 recorded sequences of the clocks were selected to be used in the work. These were analyzed using Mr. Zinovieff’s MUSYS digital system, one of the first dedicated computer music environments anywhere. According to Mr. Zinovieff in the liner notes for the disc, the composer prepared a “rough penciled graphical score of the whole piece… Here was a layout of the tensions, mood and forms of the whole… A very rough indication of the sounds was given (e.g. bell, tick-tock, clang, dong, crash, etc.).” The work then fell to Mr. Zinovieff to make it happen, and he created the work by programming the digital controllers of his otherwise analog studio to “call up a sound or sounds, to start or stop recording, to filter, amplify, distort and so on.” While pulse is the main idea of the piece, there are a surprising variety of sounds heard throughout, and the layering and distortion of regularity produces quite a dream-like character overall. The low-fidelity quality of many sounds dates the work, but the effect is rather similar to black-and-white films—there is much texture and graininess in the work that adds to its fantastical yet nostalgic character.

While Mr. Zinovieff reports that Chronometer was originally mixed onto eight tracks, then reduced to four for the premiere performance, there are no indications given as to spatialization strategies. In listening to it in 4.0 surround, it becomes clear that the different sequences of material are placed in different channels. While repetitions or variations of these sequences may shift from one channel to another, there does not appear to be any explicit movement of sound between or around the channels. Given the mostly percussive nature of the material, the localization of sounds is clear and quite effective. The effect is of being up inside the clock tower, hearing the sounds of the mechanism from all around.

Beyond the LP issue of Chronometer, the work otherwise more or less disappeared. The EMS Putney Studio closed down and moved, and materials were put into storage. The eight-track tape has never been recovered, but thankfully, the four-track tape used for the premiere was found in storage. And, thanks to this SAM release, Chronometer can have a new life.

The other historic work on this disc is more of a “classic,” having been released on a number of recordings and heard in numerous concert performances. Jonathan Harvey’s Mortuos Plango, Vivos Voco (1980) is one of the most successful pieces of digital analysis/synthesis, and one of the most important early works to come out of IRCAM at time when experimentation seemed to dominate musicality. This work has been much studied and discussed, so little need be said of the music, beyond a reminder that all the materials are derived from analyses of a church bell from Winchester Cathedral and from a choir boy chanting on a single note. I have listened to Mortuos Plango, Vivos Voco many times, both on recording and in concert. But, until I heard it at a concert in Paris at the Cité de la musique in June 2008, I had somehow overlooked the important fact that it was conceived as a four-channel work. Hearing it in surround was a revelation, I must say. The magnifying and manipulation of the bell partials are spread between channels at times, and percussive vocal effects dart around the listening space. The spatialization adds another very important element to this compelling, beautiful work. Again, SAM has done the community a great service in releasing Mr. Harvey’s classic computer work on DVD.

Javier Alvarez has been a stalwart of the UK electroacoustic scene from the early 1980s (he has since returned to Mexico, his homeland). Temazcal (1984) for maracas and electroacousics has proven to be extremely popular since its premiere in London in early 1985. The piece closes with a fragment of a traditional Mexican folk tune played on a harp. Hints of this music appear prior, but radically transformed. The maracas perform almost throughout the piece, and add a strong element of rhythm but also high-frequency transient energy. Much of the rest of the material is rhythmic as well, but explores different sonorities and registers. In the liner notes, it states that the piece was originally created for four channels, at first on analog tape and then later transferred to digital. The aural impression is of spatial ambience, with the maracas presented at the front of the listening area, as if the part were being performed onstage. There is much energy Temazcal, and the spatialization enhances the presentation by enabling the listener to hear into the textures more clearly.

Nunu Wadudu (2008) by Mira Calix is a “remix” of recorded performances of an earlier work, Nunu, a soundscape work based on insect sounds primarily. A collaboration with The London Sinfonietta resulted in a version for soundscape and instruments (bass clarinet and string quartet). Ms. Calix originally hails from South Africa and works as a DJ in the Intelligent Dance Music (IDM) scene along with her work as a composer/sound artist. The immersive quality of soundscapes is notable in this work, and the music carries a suspended, ambient quality throughout its 12 minute duration. Nunu Wadudu presents an extremely rich soundworld, combining insect-like instrumental sounds with recordings of actual insects and birds. Over the course of the piece, there is a gradual evolution toward more harmonious sonorities, and this formal shaping works nicely. The spatialization adds greatly to its immersive quality, as one would expect. Nunu Wadudu is an interesting discovery for this listener who was until this release unaware of Ms. Calix’s work.

Nunu Wadudu is the only piece on the disc that claims to be mixed for 4.1 rather than 4.0. The subwoofer element is too present for home listening, to my ears, and as there is no beat or pulse to be conveyed, as there would be in dance music, I’m not sure the low frequency energy is required here. In any case, Bass Management is a difficult issue in making surround mixes for DVD-Video release, and I noticed the subwoofer kicking in for the other works as well (especially the Alvarez). It would be necessary to adjust the controls for one’s system to avoid this, presumably.

Altogether, Recovery/Discovery is an important release, for enabling listeners to hear important historical works in quadraphonic sound as they were intended, and for introducing a powerful new voice. For those who may not have a surround-sound system to listen to the DVD on, the other side of the disc contains a CD version of the material, presented in stereo. The production quality is excellent (subwoofer issues as noted above aside). One hopes that SAM will continue to release important material on painstakingly produced recordings such as this one.