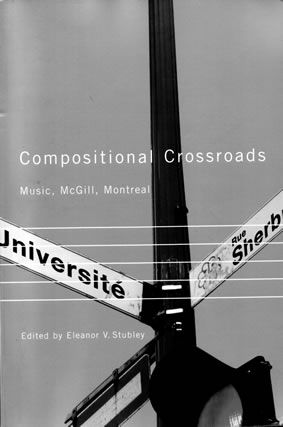

Eleanor Stubley, editor: Compositional Crossroads: Music, McGill, Montreal

Hardcover/softcover, 2008, ISBN 978-0-7735-3277-9/978-0-7735-3278-6; CAN$ 85.00/32.95, 384 pages, illustrated, chronology, appendices, name index; McGill-Queen’s University Press, 3430 McTavish Street. Montreal, Quebec H3A 1X9, Canada; telephone (+1) 514-398 3750; electronic mail mqup@mcgill.ca; Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario K7L 3N6, Canada; telephone (+1) 613-533 2155; electronic mail mqup@queensu.ca; Web www.mqup.ca/.

Reviewed by Osvaldo Budón

Montevideo, Uruguay

Compositional Crossroad is a collection of articles written by

composers, musicologists, and students who have been associated with the

Faculty of Music, McGill University, between 1970 and 2004. The book takes

as its object the emergence of McGill as a center of new music in Canada,

and focuses mainly on the explosion of new music activity that took place

at the Faculty during the second half of the twentieth century.

Compositional Crossroad is a collection of articles written by

composers, musicologists, and students who have been associated with the

Faculty of Music, McGill University, between 1970 and 2004. The book takes

as its object the emergence of McGill as a center of new music in Canada,

and focuses mainly on the explosion of new music activity that took place

at the Faculty during the second half of the twentieth century.

The study is articulated in two parts. In Part One: Mapping the Infrastructures of the Faculty of Music, McGill University, as a Center for New Music, Robin Elliott offers insight into the pioneering contribution of István Anhalt to the development of the composition program; alcides lanza, interviewed by Meg Sheppard, speaks about the birth and development of the Electronic Music Studio; and Paul Pedersen writes about the history of McGill Records. John Rea remembers the impact of the visit of foreign composers to the Faculty of Music, James Harley reflects upon how composer-performer collaborations influenced his compositional approach, and Laurie Radford evaluates some current directions in technological and artistic development.

Part Two: Composer-work studies consists of a number of essays where selected works by important composers who teach or have taught at the Faculty of Music are approached analytically. Bruce Mather contributes “The Lost Recital: An Analysis of Bengt Hambraeus’s Carrillon for Two Pianos,” Pamela Jones “The Soles of the Feet: alcides lanza Reconnects with his Roots,” and Neil Middleton “Hidden Meaning in Brian Cherney’s Die klingende Zeit.” Steven Huebner authors “Bruce Mather’s Théâtre de l’âme,” Jérôme Blais “’Music under the Influence’: on la nécessité extérieure in the Music of John Rea,” and Patrick Levesque “Illusions, Collapsing Worlds, and Magic Realism: The Music of Denys Bouliane.”

Eleanor V. Stubley, Director of Graduate Studies of the Schulich School of Music, McGill University, serves as editor of Compositional Crossroads. Her “Introduction: Crossroads” offers valuable historical background that prepares the reader to fully apprehend the significance of the articles that follow. Drawing upon a wealth of sources, she is able to present a thorough yet compact account of the evolution of Music at McGill University, which she casts against the background of important social and political events.

She further provides an introduction to both parts of the book, and contextualizes authors and their methodological approaches by means of brief biographical sketches placed at the beginning of each chapter. Ms. Stubley also contributes the closing epilogue: “The Schulich School of Music: Hearing the Future.”

The book includes a chronology and two appendices. Commercial recordings of the works cited in the body of the study are listed in Appendix one, while the document “The Aims and Philosophy of McGill University Records (1988)” is included as Appendix two.

This review will consider in some detail only the articles included in Part one.

In “István Anhalt and New Music at McGill,” musicologist Robin Elliott examines the career of Mr. Anhalt as a composer, teacher, theorist, and administrator between his arrival at McGill from Europe in 1949 (aged 29) and his departure to Queen’s University in 1971. Throughout the article, the author—who is Director of the Institute for Canadian Music at the University of Toronto— expounds the significance of this career in the context of the development of McGill’s Faculty of Music.

Budapest-born Anhalt had studied under Zoltan Kodály in Hungary and Nadia Boulanger in France. In the words of his former student William Benjamin, he was “more the exception than the rule among émigré intellectuals in being willing to take a serious, non-condescending look at his new surroundings” (p. 36). For Mr. Anhalt, the lack of a new music scene in his new country was “a good situation in which to get work done,” (p. 35) and hence he made it his mission to introduce new music to Montreal.

Often bringing in the voices of some of Mr. Anhalt’s colleagues, former composition students, and that of the composer himself, Mr. Elliott narrates his adaptation to the new surroundings, his teaching style, the growth of his reputation as a composer, his intense engagement with electronic music from the late 1950s (noting that his first contact with this music was through a CBC broadcast of Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Gesang der Jünglinge), and his interest in the creative exploration of the human voice he developed in the 1960’s.

István Anhalt, who according to Mr. Benjamin, was “committed to the notion that music was… an ever expanding domain of knowledge and possibility, rather like science” (p. 34), is remembered as an inspired pedagogue and a key figure in the establishment of the Electronic Music Studio (EMS) and the introduction of the graduate program in composition in 1968.

At the end of his article, Mr. Elliott states: “Anhalt institutionalized and validated the links between music and scientific inquiry at McGill, and thus in a sense laid the groundwork for further developments in that field, up to and including the creation in 2001 of the Center for Interdisciplinary Research in Music, Media and Technology” (p. 48).

In the following chapter, “A brief History of McGill University’s Electronic Music Studio,” alcides lanza—director of the EMS from 1974 to 2004 and Director Emeritus since then— is interviewed by Meg Sheppard.

Mr. lanza considers that McGill’s Electronic Music

Studio was born on 16 June 1964, when an Oscillator Bank and a Spectrogram

(both instruments built by inventor Hugh Le Caine) were delivered to the

Faculty of Music. Mr. Anhalt, who had been collaborating with Le Caine

for several years, became the first EMS director. Subsequent directors

of the first electronic studio to be established in the province of Quebec

were Paul Pedersen (1971-1973), Mr. lanza and Bengt Hambraeus (1973-1974),

and then Mr. lanza (1974-2004). In 2004 the Electronic Music Studio was

renamed Digital Composition Studio and Sean Ferguson was appointed its

director.

Teaching activities at the EMS, Prof. lanza recalls, started in 1968 in

connection with the launching of graduate programs in composition and musicology

(previously, the facilities were dedicated exclusively to the creation

of new works by composers on the staff and invited composers). Until the

early 1980s, when a Synclavier II was purchased and the McGill EMS became

the first digital studio in Canada, the equipment consisted mainly of Le

Caine and Moog instruments. Another important articulation in the EMS history

took place in 1987, when Bruce Pennycook was hired to develop a music technology

area at McGill. This new area was to share some facilities and have overlapping

areas of interest with the EMS.

Mr. lanza also refers to the involvement of the EMS and the Group of the Electronic Music Studio (GEMS) —in partnership with the Composition area— in the organization of the McGill Contemporary Music Festivals from 1982 to 1989. Among other performance milestones, he recalls the festival organized in 1989 to celebrate the studio’s 25th anniversary.

Toward the end of the interview, Mr. lanza evaluates the historical significance of the studio in the following terms: “From its modest beginnings in the Redpath coach house, the EMS has played a major role in the development of sound recording, music technology, digital composition, and a myriad of recent interdisciplinary research and initiatives” (p. 70). The legacy of the McGill EMS is seen by its Director Emeritus as “the training of generations of electroacousticians in the production, promotion, and dissemination of electroacoustic music in all its forms” (ibid.).

Composition professor since 1973 and former Dean, John Rea authors the third chapter of the book: “Better than a thousand days of diligent study is a day with a great teacher: visiting foreign artists residencies at McGill’s Faculty of Music, 1975-1981.” Through reference to the circumstances associated with the guest artist residencies of Mario Bertoncini (Italy), Edgar Valcárcel (Peru), Mariano Etkin (Argentina), and Makoto Shinohara (Japan), Mr. Rea is able to recreate the singular atmosphere that existed at the Faculty of Music and in Montreal in the middle to late 1970’s: “A social, artistic, and educational environment that seems almost impossible to imagine today” (p. 74). The Faculty of Music had been recently relocated to a new building and several new staff members, coming from around the world, had joined Bruce Mather in the composition area between 1971 and 1973: alcides lanza (Argentina), Brian Cherney (Canada), Bengt Hambraeus (Sweden), Robert Jones (USA), Peter Paul Koprowski (Poland), and John Rea (Canada).

The Canada Council for the Arts sponsored the visits to McGill of the composers named above with funds from the Visiting Foreign Artists Program. During their residencies, the guest artists were to assume teaching responsibilities at the Faculty of Music, and to become actively engaged in concerts and other new music-related activities. For a period lasting approximately one semester, student composers discovered and confronted other poetics through contact with the musical languages that were cultivated by each one of the visitors.

From Mr. Rea’s writing the reader gathers that the Faculty in those days resembled something like a unique crossroad where “east met west” and “south met north” for the benefit of everyone, the music students in the first place. The author draws a human and artistic portrait of each guest composer, providing a thorough biographical background and a description of their main activities while in Montreal. He also offers some insight —remarkable both in depth and style—into selected compositions. Furthermore, he reconstructs in considerable detail several public concerts where the visiting artists participated as composers and/or performers. This allows him to share with the reader his own recollection of how their music was heard at that time.

Mr. Rea’s writing remains

intense and engaging throughout this lengthy essay. One feels that his

reflections on the nature and value of the work of his foreign colleagues

are also the background against which he is seeking to apprehend his own

artistic singularity.

Paul Pedersen contributes the article “McGill University Records,

1976-1990: A Brief History.”The author’s attachment

to McGill began in 1966, initially in connection with the EMS. Mr. Pedersen,

who in 1965 completed the first fully computerized composition written

in Canada, would stay at McGill until 1990, where he was to be among the

founders of McGill Records, and also serve as Dean of the Faculty of Music

for a decade (1976-1986).

According to Mr. Pedersen, the story of McGill Records starts in 1974, at the Chopin Academy of Music in Warsaw, Poland, when he by chance met Wieslaw Woszczyk—then a sound recording student at that institution—who was to become a key figure in the development of the Sound Recording Program at McGill. McGill Records was formally initiated in 1976, while the Faculty of Music was undergoing a period of significant growth. Mr. Woszczyk was to be the recording engineer, Donald Steven the recording producer, and Mr. Pedersen the executive producer. McGill’s own recording studio became operational in 1980. Until then, microphones had to be rented out and tape recorders borrowed from the EMS for recording sessions.

The aim of McGill Records was, in the first place, to promote the Faculty of Music through recordings of faculty performers, including student ensembles, and the music of faculty composers. Featuring other Canadian performers and composers came next in the order of priorities. Recording pieces from the repertoire that were not commercially available was also a guiding criteria for the choice of projects. One of the first releases was Percussion, which featured music by Canadian composers performed by students in the McGill Percussion Ensemble directed by Pierre Béluse. This disc won the first prize for the Best Chamber Music Recording in the 1979 Grand Prix du Disque (Canada).

The author offers a very thorough historical account of the development of McGill Records through its different phases. He provides very precise information and includes several illustrative —and often amusing— anecdotes. Mr. Pedersen’s prose, both elegant and direct, contributes to keep the reader focused as he describes in some detail how numerous artistic, financial, legal, and administrative issues were dealt with over the years.

By 1990, when Mr. Pedersen left McGill to become Dean of Music at the University of Toronto, 36 recordings had been issued. Works by McGill composers amounted to 35% of the total playing time. The author concludes: “I believe that whatever success McGill Records had during the period from 1976 to 1990 was due in no small part to the fortunate coincidence of the right staff, students, facilities, and opportunity all coming together at a crucial time in the history of the Faculty of Music. Today it is widely perceived that the McGill Faculty of Music has become the pre-eminent Canadian Music School, and McGill Records probably helped to create and solidify that perception” (p. 128).

In “The making of new music: Composer as collaborator,” James Harley—currently a professor of Digital Music at the University of Guelph—recalls several of his collaborative experiences with performers, and reflects upon how these collaborations influenced his compositional approach and contributed to give form to his work.

Attending Iannis Xenakis’s

seminars at Université de Paris

and working with the UPIC system at the Centre d’Etudes de Mathématique

et Automatique Musicales (CEMAMu), did much to shape Mr. Harley’s

musical thinking. Having learnt mathematics on Xenakis’s advice,

and while a postgraduate student at the Chopin Academy of Music in Warsaw,

he read an article by Douglas Hofstadter on nonlinear functions that exhibited “chaotic” traits.

He soon started to work on developing ways to apply non-linear functions

to music composition. The search for computing resources and the opportunity

to develop programming skills led Mr. Harley in 1988 to the doctoral program

at McGill, where Bruce Pennycook was developing computer music resources.

While a doctoral student, Mr. Harley developed —both within the Faculty

of Music and in the larger context of the Montreal new music community—fruitful

collaborative relationships with various ensembles, conductors, and individual

performers. These experiences, that were to be meaningful in the development

of his compositional aesthetic, included collaborations with the McGill

Symphony Orchestra and the McGill Percussion Ensemble; conductors Lorraine

Vaillancourt and Veronique Lacroix; the ensemble Kappa and its director,

Philippe Keyser; percussionist D’Arcy Gray; pianist Marc Couroux;

and the duo formed by pianist Brigitte Poulin and violist Laura Wilcox.

The author opposes the “Ivory Tower” composer, instead opting for the model of “a composer that collaborates with performers as mutual partners in an evolving process” (pp. 129-130). He explains on a case-by-case basis how specific compositions were conceived and developed in the context of a creative exchange between composer and performer. Score excerpts of the compositions illustrate the discussion. The issue of the levels of technical difficulty that arise from exploring the algorithmic compositional applications of chaos theory comes more than once to the forefront of Mr. Harley’s reflections. His concern with the fact that “performers need to be able to find the value and beauty in a composition if they are to do their part in conveying the music to the listener” (p. 132) resonates throughout the essay.

In “From

Mixed Up to Mixin’ it up: Evolving Paradigms in Electronic

Music Performance Practice,” composer Laurie Radford considers some

of the fundamental changes that music making—largely in relation

to technological developments—underwent over the second half of the

twentieth century, and evaluates current directions in technological and

artistic development. “Technologies born of a particular need,” says

the author, “in turn bring about changes in their maker and their

maker’s world” (p. 154) By way of a quote from Mike Berk, he

brings in a notion that is central to his essay: “it’s the

electronic music studio—instruments, processing gear, and recording

and editing equipment—that inaugurates a new sonic paradigm, confounding

our standard definitions of what ‘instruments,’ ‘composition,’ and ‘recording’ are” (quoted

on p. 155).

For Mr. Radford—a professor at City University of London at the time

of publication—“the evolving technical facilities to access,

evaluate, fragment, and reshape sound and image documents in powerful and

efficient yet relatively simple ways” (p. 154) lay at the heart of “the

growing inclination towards the alchemical mixing of cultural products

as artistic material and experience” (pp. 155-156). The author elaborates

at length upon the concept of the “mix.” He offers several

definitions for this term, ordered, one might say, according to a “scale

of mixness” covering the ambitus between the simple mixture of acoustic

and electroacoustic sound sources and the mix of live performance, pre-programmed

response, and cyber-space connectivity. The concept is also evaluated within

the framework of the threefold paradigm of present-day music-making (oral

tradition, written music, and electroacoustic music) proposed by François

Delalande. Through reference to the ideas set forth in Jacques Attali’s

book Noise, Mr. Radford proposes a fourth paradigm in which “an

emerging cultural imperative to ‘mix’ and ‘remix’ the

sounds and images of the world erases the historic and aesthetic boundaries

distinguishing Delalande’s paradigms” (p. 151).

Mr. Radford, who believes that “the ‘mixed’ work has been the territory of choice for a unique range of expression and material exploration” (p. 156), refers to the activities of the Group of the Electronic Music Studio (GEMS) —founded in 1982 at McGill’s Faculty of Music— to provide reference and context for his discussion.

A former GEMS member himself, the author sees the group’s work as an example of “the ongoing tendencies [in electronic music performance practice] towards an integration of a broad field of sound sources and instrumental forces” (p. 151).

I trust that anyone interested in gaining a better understanding about the singular nature of Canadian music will enjoy readingCompositional Crossroads as much as I did. I found the book to be dense in concepts and information, very well written, and edited most carefully. While each chapter is, to a large extent, an autonomous text that can be read independently from the others, the whole is clearly more that the sum of its parts. I find particularly accurate the editor’s description of the book as “a series of snapshots that, flashed one after the other in quick succession, capture the vibrant life of a prestigious North American music academy at the turn of the twenty-first century standing on the threshold of a new beginning as the McGill University Schulich School of Music” (p. 4).

The fact that the EMS played a central role in the development of the “new” at McGill is likely to become apparent to the reader from the evidence provided by various chapters in the book. Hence, I believe that any course on the history of electroacoustic music will benefit from including Compositional Crossroads in its bibliography.